"Glitch Mode" and Concerted Scans

the longue durée history of human communication; today only, a new modality in scientific visualization; concerted scans

Long ago, humans communicated by drawing on caves and making pigments out of plants and rocks.

As the scale of human civilization increased, new means of communication allowed societies to manage increasing complexity. The ancient Sumerians developed cuneiform, a writing system which allowed them to create receipts, manage inventory, and submit formal written complaints.

Over time, societies underwent a broader transition towards codifying knowledge in writing. Here’s what Alice Maz writes about this:

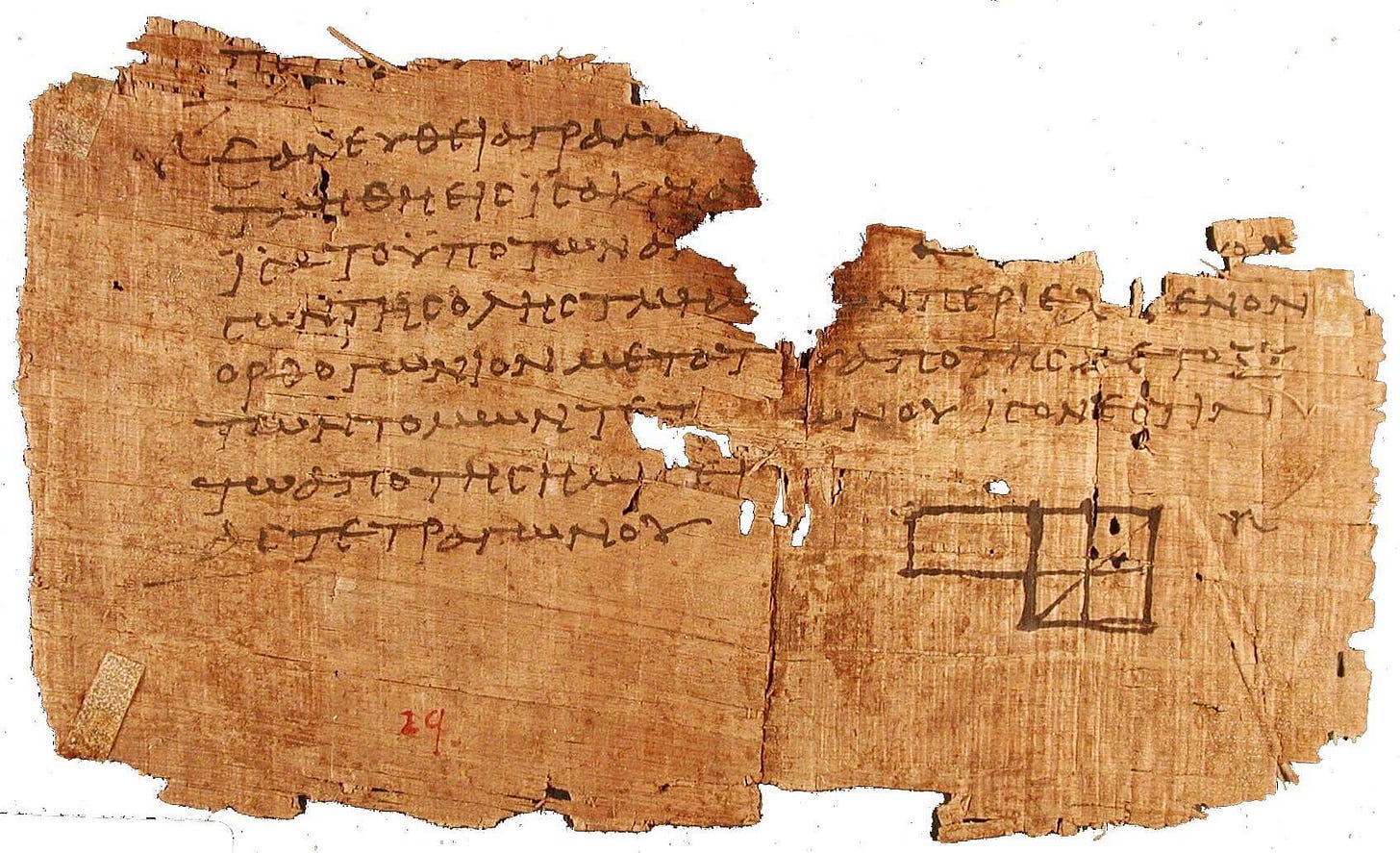

The advent of written language allowed oral cultures to be centralized and canonized, relieving the burdens and lossiness of memory. Traditions were made into texts, singular and authoritative. Externalizing memory to papyrus or parchment enormously expanded the scope of what could be retained. It also eliminated the necessity for exactitude and endless repetition when instructing students, allowing for a stronger focus on meaning and interpretation.

This shift vastly expanded the amount of knowledge available to any single scholar, and streamlined the educational process. Taken together, these effects attenuate the impact of the burden of knowledge and made it possible for individuals to attain higher levels of mastery in a given discipline.

The immense cost and difficulty of manuscript production created an inherent centralization in the scientific progress. The advent of the printing press changed this, dropping the cost of disseminating information by orders of magnitude and making it possible to share and spread information at unprecedented speed. The need to organize and share this information led to the formation of the modern system of scientific journals from the 1660s onwards.

The advent of computing has further transformed scientific communication, making it possible for scientists all across the world to collaborate, share results, and visualize data. Thanks to projects like arXiv, bioRxiv, and ChemRxiv the cost of reading and writing scientific manuscripts has fallen to virtually nothing, and public code and data repositories make it possible to build on others’ results in an open and transparent way.

Sadly, the forms of communication that scientists current employ are ill-adapted to the current millennium. PDF articles are untethered from the underlying code and data, fail to show 3D structures accurately, and are difficult for people with short attention spans to focus on. To address these problems, we’re happy to be sharing our latest feature…

…Glitch Mode!

We’re launching a new visualization mode on Rowan that makes it possible for molecular structures to look all cyberpunk and futuristic. It’s tough to share what this looks like without a video, so we recommend you just go ahead and try it yourself.

Glitch mode is disabled by default, but can be enabled by clicking the multicolored button found in the bottom left of the molecule viewer. We advise users with photosensitive epilepsy not to enable glitch mode.

This feature will only be live for today, so please have as much fun as possible.

Rowan acknowledges the impact of important cultural works like Blade Runner, Neuromancer, The Matrix, 2814, and Allston on glitch mode.

Concerted Scans

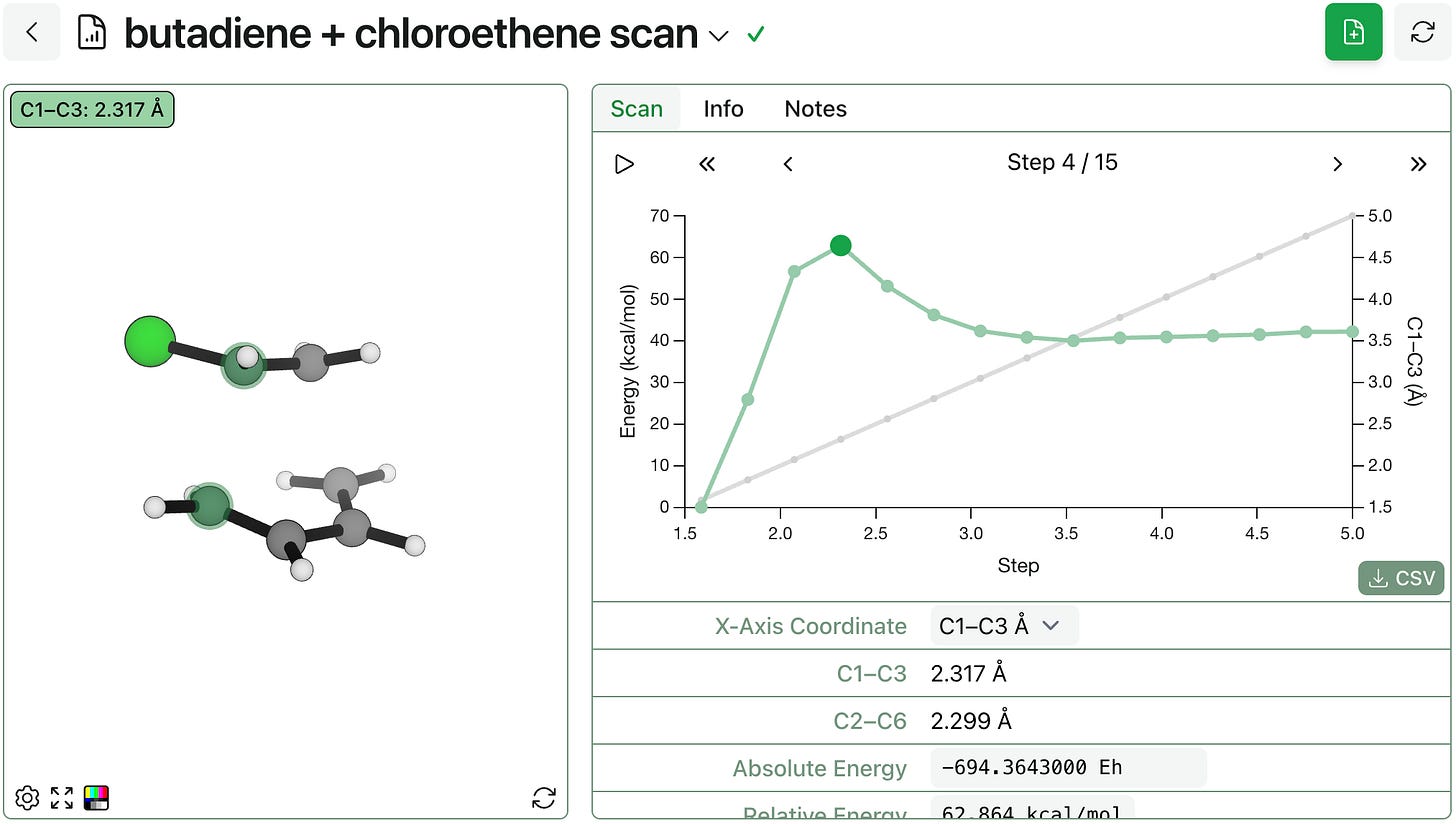

On a more serious note, you can now run scans along two or more internal coordinates simultaneously. This is nice for e.g. finding cycloaddition transition states, where two bonds are forming or breaking simultaneously.